One: Going home

Vincent O’Sullivan has written a 14-episode account of Ralph Hotere’s journey home. The number recalls Hotere’s use of the number, his referencing of the Stations of the Cross and of his 14 siblings. Frustratingly, the full version is only available to subscribers (when did the Listener change that?).

Two: Favourite birds (my son will be so cross that I haven’t used the proper full names, but the truth is, I can’t remember them)

godwit

kingfisher

pelican

spoonbill

robin

shag

plover

kea

bellbird

crane

heron

mandarin duck

black cockatoo

superb lyrebird

Three: Books that got me through my childhood, and my children’s

Corduroy, Don Freeman

Any of the Frances books, Russell Hoban (illustrated by Garth Williams)

Tell Me What It’s Like to Be Big, Joyce Dunbar (illustrated by Debi Gliori)

Mr Gumpy’s Outing, John Burningham

Big Momma Makes the World, Phyllis Root (illustrated by Helen Oxenbury)

The Ramona books, Beverly Cleary

Big Sister and Little Sister, Charlotte Zolotow (illustrated by Martha Alexander)

Virginia Wolf, Kyo Maclear (illustrated by Isabelle Arsenault)

Come On, Daisy!, Jane Simmons

The Raft, Jim LaMarche

The Tiger Who Came to Tea and the Mog books, Judith Kerr

Dogger and everything else, Shirley Hughes

far too much by Noel Streatfeild

Anne of Green Gables and all the rest, LM Montgomery

bonus: Kitten’s First Full Moon, Kevin Henke + about a hundred others

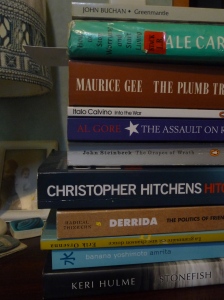

Four: Authors I’ve found myself consuming in bulk

George Perec

Italo Calvino

Primo Levi

Laurence Fearnley

Janette Turner Hospital

Nigel Cox

Sara Maitland

Jeanette Winterson

Maurice Gee

Philip Pullman

Ann Patchett

Jim Crace

Michael Ondaatje

(see the children’s list above)

Five: Foods that make life better

avocado

pistachios

chocolate

smoked salmon

salad, lots of it

roast chicken, then chicken soup

oranges

peaches

eggplants

poisson cru

tomatoes

fennel seed and olive oil biscuits

bacon

lasagne

Six: 14-letter words

Seven: What I want in a house

a chair by a window, just for reading

a kitchen that I can eat, cook, talk, and read in

a space for the kids to play

a front porch

a sheltered space to eat outside

plenty of trees

a glasshouse

vegetable patches

a workspace

bookshelves in every room

a woodburner

insulation

flowers

light

Eight: Condiments, loosely interpreted

lemons — fresh, juiced, zested, preserved

honey

mustard

fennel seeds

yoghurt

parmesan

sea salt

pepper

tomato sauce

mint

coffee

a book

a friend

quiet

Nine: Punctuation that makes text prettier

fanciful ampersands

the Oxford comma

double quote marks

em-dashes

en-dashes

ellipses

semi-colons

full stops

question marks, sparingly

well-placed commas

accents

tidy, well-aligned bullet points

parentheses, occasionally

spaces

Ten: Plants I like to have in my garden

tulips

crocuses

sweetpeas

roses

azaleas

ferns

mint

thyme

sage

peas

beans

lettuces

zucchini

potatoes

Eleven: The elements of a fine day

rain

sun

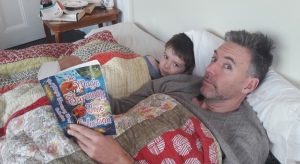

a small boy’s arms around my neck

that first cup of coffee

a shower

a walk, run, or yoga class

music

writing

banter

a kiss

friends

seeing something through my children’s eyes

lunch

supper

Twelve: A 14-year-old dancer

Thirteen: Colin McCahon’s Stations

Fourteen: A sonnet, of course

Not in a silver casket cool with pearls

Or rich with red corundum or with blue,

Locked, and the key withheld, as other girls

Have given their loves, I give my love to you;

Not in a lovers’-knot, not in a ring

Worked in such fashion, and the legend plain—

Semper fidelis, where a secret spring

Kennels a drop of mischief for the brain:

Love in the open hand, no thing but that,

Ungemmed, unhidden, wishing not to hurt,

As one should bring you cowslips in a hat

Swung from the hand, or apples in her skirt,

I bring you, calling out as children do:

“Look what I have!—And these are all for you.”

Edna St. Vincent Millay